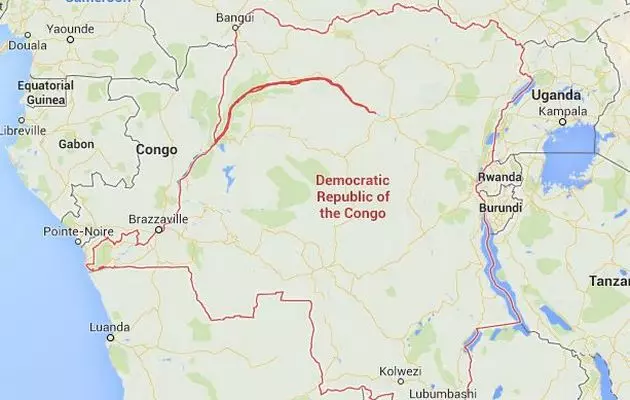

Map of DR Congo. File photo

Image by: Google Maps

It all began with a love affair a year ago between a Bantu and his Pygmy mistress, a tryst that so unnerved the enemy peoples of Congo’s troubled Katanga province that war broke out.

Fighting between the Bantu land-owners and the hunter-gatherers of the Twa Pygmy groups – pitting bows-and-arrows against machete blades — has since caused some 80,000 people to flee their homes in the mineral-rich province in southeast Democratic Republic of Congo.

But in this village of Mukondo, home to some 1,300 refugees from both sides, the traditionally warring Bantus and Pygmies are learning to live together at last.

“When the two communities fought, those who were opposed to war fled, and this is how I came to host ‘moderate’ Bantus and Pygmies here,” said Daniel Mwandja, the Bantu village chief.

Since colonial times, cohabitation has never been easy between the two, with the Bantus accused of exploiting the Pygmies, paying them meagre wages, or in alcohol and cigarettes, and generally treating them as inferior beings.

The Pygmies’ nomadic lifestyle is increasingly under threat from deforestation, mining and extensive farming by the Bantus. In March 2009, according to an African NGO, black magic beliefs led to three Pygmies, two of them children, being raped by soldiers who were seeking to achieve “invulnerability.”

Pygmies, said Rogatien Kitenge who works with the community, were very frustrated about the way they were treated, “like vassals of the Bantus who don’t have the same rights.”

Kitenge said it was regretful that neither the army nor the UN force could deploy more troops in Katanga province.

“Pygmies and Bantus are kept apart”

The latest trouble erupted in a village that is some 200 kilometres away by foot, in the province’s northern Tanganyika district. “A Bantu was surprised in flagrante delicto of adultery with a Pygmy woman. After that the situation deteriorated,” Mwandja said.

But in Mukondo, which was home to some 1,100 people until the wave of mostly-Pygmy refugees doubled its population, the two communities are living in harmony.

“When I welcomed these displaced people here, specially the Pygmies, I treated them like people in distress, not like cheap labour,” said Mwandja.

That is not the case elsewhere.

In the camp of Kamala, close to where the conflict started, “Pygmies and Bantus are kept apart,” said Alimata Ouattara of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, which oversees Mukondo. “I’ve asked why several times… I’ve never received a convincing reply.”

Bantu refugee Kungwa Kaumba said she was originally fearful of living alongside Pygmy people but had now changed her mind. Elsewhere, “when they thought they were being badly paid they’d quarrel, but in Mukondo, things are better.”

In the fields, Bantu and Pygmy women work side by side, even sharing food or loaning pans and utensils to newcomers who left home in a panic.

The women also meet each week to talk and to keep the peace. “I tell them this conflict … erupted because of adultery and that we should avoid new problems,” said Anna Muganza, 35, a Bantu refugee leader.

“I also insist they mustn’t steal cassava from the fields.”

Conditions are far from easy in the camp, which has no drinking water or school and where the nearest health centre is 22 kilometres away. Because of the lack of medical care, nine women died in childbirth and at least 19 children died of illness in the last few months alone.

But many Pygmies say life there is not so bad after all. “The Bantus who live here are better than the others! We were welcomed and given food to eat,” said their chief Sango Shabani Esau.

“The quantity of cassava we get paid here is better than at home and sometimes they even give us an extra two! And when a Twa woman has no wrap, a Bantu woman will give her one.”

He admits his people miss hunting, however, after Mukondo chief Mwandja banned the Pygmies from making new arrows in the interest of peace.