Elly Rwakoma is the man behind the famous pictures of former president Idi Amin in the swimming pool. One of those pictures almost got him killed, writes CAROL NATUKUNDA.

They were friends who often hang out together, had a cup of tea or simply spent time on indoor games. But that was before Idi Amin became president and all hell broke loose.

Soon, Rwakoma realised that the man he loved and trusted had turned into a monster. People were dying under mysterious circumstances. Others simply disappeared. Initially, Rwakoma gave Amin the benefit of the doubt, like the true friend he was. But as he would later painfully discover, the Amin he called a friend was something else.

“He killed my uncle and three cousins and their children,” Rwakoma recollects, adding: “Archbishop Janani Luwum and Uganda’s first prime minister Benedicto Kiwanuka were both killed. It was painful to accept. And for me, that was it. I hated Amin.”

Rwakoma’s assassinated uncle was Nekemiah Bananuka, the then secretary general of the Ankole Kingdom.

“I was angry with Amin. Very angry. I wanted to confront him, but on second thought, I decided to keep quiet. If he got to know that there was a connection between me and Bananuka’s family, he would kill me too,” Rwakoma narrates.

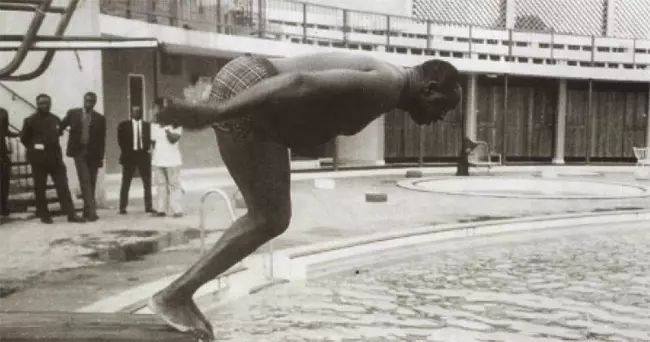

But Rwakoma planned the perfect revenge. Having been Amin’s close confidant and chief photographer, he had all the pictures of Amin’s private life, his children and wives. One of the famous pictures he took was when Amin was diving into the swimming pool at Apollo Hotel,now sheraton Hotel in Kampala. Amin was only in swimming shorts.

There were several other pictures Rwakoma took while Amin was swimming, sometimes alone, sometimes with his children at Jinja Club, which had been his favourite hangout since the days when he was still a commander under the Obote I regime.

Although Amin had these pictures safely kept away, Rwakoma had the negatives which he developed. Determined to scandalise the dictator, Rwakoma sold the pictures to an international photojournalist.

Amin diving into a swimming pool

A few days later, the legendary photograph of Amin diving into the swimming pool was published in the New York Times with a caption: Is Amin sinking or swimming?

“When that picture was published, I knew I was in trouble,” Rwakoma recalls.

He was right. The next thing he knew, Amin’s bad boys were storming his studio and shop in Jinja and hunting for him.

“That day, I was there, but I was dressed in shorts and slippers so they thought I was just an attendant. They asked me: “Where is this man who is so mean to our president?’ I told them he had gone to the bank. They searched everywhere and took all the negatives I had. Some of my equipment was also destroyed before they left. I sensed trouble. On the advice of a friend, I fled the country,” Rwakoma recalls.

That afternoon, he left his shop open and walked to his car, which he had parked not far away from his shop. He was careful not to look suspicious.

“I drove to the petrol station, filled my tank and immediately drove to the Busia border. I did not tell my wife where I was going. Our seven children were still very young and there was no time to drive home anyway,” he says.

At Busia, Rwakoma parked at the border and crossed into Kenya on foot with the help of a policeman.

“I had an Asian friend there who helped me,” he says.

Luckily, Amin’s tyrannical regime was coming to an end, so Rwakoma spent only three months in exile. He re-united with his family as soon as Amin was out of power.

How he became Amin’s photographer

Rwakoma had been a photographer since his childhood. While in P3, a relative gave him a gift. It was a pinhole camera — a tiny box without a lens, but with a tiny hole in the centre of one end. Little Rwakoma, then at Kabira Primary School in Bushenyi district, did not know how to use this tiny box. He took it to his teacher.

“The teacher took me to an old man who used to take pictures and he taught me how to take pictures and develop a film manually, sometimes using shading,” he recalls.

Growing up in a peasant family, Rwakoma realised he could make money with his small camera.

“I made money by taking pictures around my village, or even at school. I charged 50 cents per picture. So if I took 12 pictures, that was quite some good money to pay my school fees,” he laughs.

Later, Rwakoma dropped out of school to make a living in Kampala just like his older brothers. He had wanted to join the Police force, but they said he was too short.

He tried to make ends meet by doing household chores for Police officers at Nsambya Police barracks, but in the end, he went back to his village in Sheema.

Using his savings, he enrolled for junior secondary education at Ruyonza SSS, before joining Kakoba Teacher Training College. But, he still did not give up photography. It was his life.

“By the time Uganda got independence in 1962, I was photographing people for money,” he says.

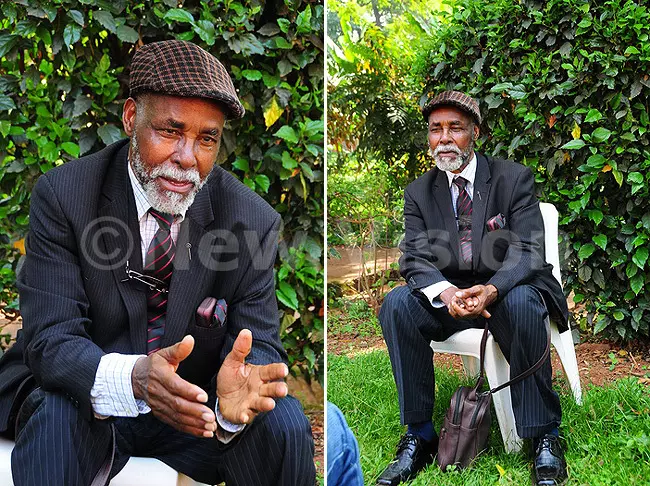

LEFT-RIGHT: Elly Rwakoma today, in his younger days and former Ugandan president Idi Amin

Rwakoma later gave up teaching, because of the measly salary he was earning, in order to concentrate on community developmental work. By this time, he was already a key figure in the Uganda People’s Congress (UPC) government, working as a youth mobiliser for the party. With connections, it was easy for Rwakoma to get training opportunities and jobs.

He went to Nsamizi Insitute for a short course in social work and social administration (SWASA) and was later attached to YMCA in Jinja as a community worker. He was then taken up for an exchange programme for a diploma in SWASA at Rochester University in New York. While there, he also upgraded his photography skills and bought up-to-date cameras.

When he returned two years later, he decided to continue with photography alongside community work.

“There is a thrill about taking pictures I cannot explain. I loved capturing people’s expressions, children and beautiful girls, which I would sell to the newspapers at that time,” Rwakoma says.

Soon, he decided to approach the presidential press unit as a photographer.

“President Obote knew me as a youth mobiliser, so I simply asked him for a job and they gave it to me,” says Rwakoma.

At the same time, he opened a shop and a studio and during his free time he would take pictures of weddings, and public figures.

When Obote was overthrown, Rwakoma continued working as a photographer in the president’s office.

“Amin had no problem with me. When he was still a commanding officer, his house was behind YMCA in Jinja where I was working and we used to meet, chat and laugh. He loved sports, including swimming. That is how we became friends. He even helped me to get funding for my project in Jinja, including completion of a youth centre for carpentry, mechanics and brick-laying,” Rwakoma says.

Even the day Amin usurped power, Rwakoma was among the first people he told.

“He called me and told me he was the president and I was happy for him. Amin was lively, so comical and friendly. I do not know where he got the heart to kill,” Rwakoma says.

Other memorable shots

Rwakoma cannot put a figure to the number of memorable pictures he might have taken of Amin. But he remembers that he was the only person that Amin took along even for his private antics.

Once, Amin made a group of British men carry him on their shoulders, while others crawled on the floor. Rwakoma was the only photographer called in to take the pictures.

“Amin used to call himself all sorts of titles, like the President for life, Field marshal and the conqueror of the British empire in Africa. He wanted to show the British that he was mightier than them,” Rwakoma says.

Rwakoma: “Amin was lively, so comical and friendly. I do not know where he got the heart to kill.”

Other famous pictures were the Clock Tower shootings in which 15 people were killed by firing squad on September 10, 1977.

“I stood at the top of a mosque downtown to take pictures of the live killings. It was chilling,” he says.

Rwakoma, however, says he never saw Amin kill anyone.

“I think most of the killings were done under his orders and at night, like the day Archbishop Luwum was killed.”

Life after exile

When Rwakoma returned from exile in 1979, he resumed his photography business. He later rejoined the presidential press unit under Godfrey Binaisa’s regime and the subsequent governments. Rwakoma remembers taking pictures of the 1980 national elections.

When President Yoweri Museveni came to power, Rwakoma served as a photographer for presidential functions for one year, before he retired.

“I wanted to concentrate on farming and give more time to my family,” he says.

The 77-year-old lives a quiet life with his wife Stella in Makerere-Kikoni. His children are all grown-up.

Incidentally, Rwakoma had met Museveni as a boy.

“Museveni was in P2 while I was in P5. We were both at Kyamatte Primary School. My memory of him is that he was a friendly boy,” Rwakoma reveals but declines to say more.

Why did he not serve Museveni a little longer?

“Because I am a UPC diehard. He has called me several times to change to NRM, but I cannot. If you are a child and your daddy gets crippled, he does not stop being your father. UPC is my parent. I cannot betray it,” he says